Below is the text of a keynote paper given on Sunday 29 May 2016 for the ‘Mediating cityscapes’ symposium, held as part of the Artists’ Film Biennial at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. It was an informal paper, in which I mainly was asked to open out some issues for the symposium. So I deliberately avoided offering an ironclad argument. But the opening out of these issues may also be of interest beyond the workshop as a partial introduction to some themes related to what I call ‘the media-urban nexus’ (not I term that I invented, I should say). The paper is more or less unchanged from the symposium, though I didn’t included most of my slide images, aside from a couple of instances where the text wouldn’t make sense without the images. In those cases I’ve either included an image or a link.

Below is the text of a keynote paper given on Sunday 29 May 2016 for the ‘Mediating cityscapes’ symposium, held as part of the Artists’ Film Biennial at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. It was an informal paper, in which I mainly was asked to open out some issues for the symposium. So I deliberately avoided offering an ironclad argument. But the opening out of these issues may also be of interest beyond the workshop as a partial introduction to some themes related to what I call ‘the media-urban nexus’ (not I term that I invented, I should say). The paper is more or less unchanged from the symposium, though I didn’t included most of my slide images, aside from a couple of instances where the text wouldn’t make sense without the images. In those cases I’ve either included an image or a link.

The media-urban nexus: histories, stakes, possibilities

What I would like to do in this short keynote is to open out a set of themes around what I will term the ‘media-urban nexus’. The media-urban nexus – a term I’ve lifted from a collaborative paper I authored with Clive Barnett and Allan Cochrane (Rodgers et al., 2014) – points to two things. On the one hand, to how the practices, rhythms and motilities of urban living compel certain uses, exposures and desires in relation to media. And on the other hand, how media forms, infrastructures, and industries inhabit – and are increasingly ‘built-into’ – urban environments. In speaking of a media-urban nexus I am not only – or even mainly – speaking of the way the city appears in media representations. Nor am I primarily referring to how large media institutions inhabit the city. Instead, I am pointing to the city itself as a mediating environment.

This way of thinking about the media and cities suggests we use the urban to rethink media; and media to rethink the urban. In so doing, it has attracted no shortage of academic debate and study. And at the same time, it has also been a lively thematic focus for a range of contemporary arts and media practice. For example, new participatory forms of site-specific art that challenge the more conventional approaches to public art often seen in urban regeneration projects. Or artistic and curatorial experiments with locational technologies, building on a long tradition of locative media arts that predates the commercialised location-based services (such as Google maps, Uber, Just East, etc.) that are increasingly ubiquitous in daily London life. Or – to give one final example that is germane to film in particular – recent interests in outdoor cinema and public screens; not just to exhibit film in new settings, but to experiment with the ambient and interactive potential of moving images in public spaces.

The programme for this symposium on mediating cityscapes lists a very diverse set of cases, examples and perspectives. It would be impossible, and probably a little arrogant, to open here with something presented as a general framework that the more focused contributions should follow. My aim is more modest. I hope instead to provide some points of reference, some historical and contemporary examples, some key concepts. In other words, things to which we might return, selectively, as the symposium unfolds.

Surfaces and Depths

It may already be obvious that this idea of a media-urban nexus is pretty vast and unwieldly. It’s a good thing, for sure, that we will have some more specific explorations later on to flesh things out. But how might we think of this ‘nexus’ at a more abstract level? One way is to think in terms of surfaces and depths.

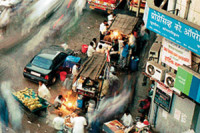

To begin with, we might think about the ways in which the city and its various architectural and infrastructural surfaces operate as mediums of communication: a vast visual canvas. This has a long history, which is captured well by David Henkin (1998) is his book City Reading. Conventionally, when we think about ‘reading’ the city, we assume a private reading experience. To be sure, not one experience, but a whole series of readings acts, across all manner of fiction and nonfiction materials. But still, an image of reading involving mind, body and text. In his historical account of antebellum New York City, Henkin however finds a city strewn, littered and adorned with words and symbols: bills, billboards, banners, painted brick surfaces, discarded newspapers. City reading, here, is about experiencing forms of communication literally built into urban spaces and city living.

In contemporary urban environments, surfaces are not only strewn, littered and adorned with words and symbols but also images – and moving images. Already, we might want to be a little cautious about using the term ‘surfaces’. It risks suggesting a two-dimensional, screenic idea of the city as a medium. If urban surfaces offer a visual canvas, they do so in ways that are distinctly environmental. Consider, for example, ‘out-of-home advertising’ – as it is called in the industry. These are the ads that ‘you can turn off’. What’s important for such commoditised images is not only the what, but the where. As Anne Cronin (who conducted an extensive study of out-of-home advertising) put it: these images align “the travel and work rhythms of the city [and] the innovation and promotion rhythms of the commodity” (2006, p. 618). So, they not only carve our urban spaces, but also temporalities. Think about our semi-automated movement through transport systems, which provides opportunities for the punctual presentation of advertising images – images as dependent on the movement of the viewer as that of the image itself. As Iain Borden put it, after witnessing ads appear and disappear on the fronts of tube escalator steps (similar to the examples shown in this promotional video): “These are temporal as well as spatial insertions, for the exact moment of intrusion is precisely judged in time as well as space, invading the psychology of the traveller at the very moment of decision-making” (2000, p. 105).

Contemporary street art perhaps exemplifies a counterpoint, but one which still draws on the environmental orientations also found in so-called out-of-home advertising. It’s perhaps a cliché to use Banksy as an example here, but what is obvious with an image such as this is that its evocation is not merely symbolic (i.e. here, evoking the idea that removing graffiti is akin to removing petroglyphs). It is that this piece – as with much of Banksy’s work – is woven into the urban fabric. The cleaner is not only deliberately proportional in size, but positioned in such a way so as to evoke the actual removal taking place at this specific site. And, it also beckons the social and political dimensions of the urban environment. The municipal worker representing a local authority, many of which often take a ‘zero-tolerance’ approach to graffiti; the regime, for example, of the City of Westminster, home to the ICA.

As its name suggests, street art entails a commitment to art using the city as a medium. For Joe Austin (2010), street art as well as graffiti invite the possibility for another ‘art city’, which works in contradistinction to the more exclusionary urban spaces of the ‘white cube’ (i.e. the quintessential urban art gallery). While Austin acknowledges that galleries are spaces that allow for the contemplation of transgressive art, they usually do so by creating distance between the space of the gallery and city. By contrast, graffiti and street art offer the potential for more serendipitous encounter, which might shake us out of our habitual and unquestioned lives. They challenge the notion that art should only exist and be contemplated in dedicated environments; and they challenge the idea that the city should remain an orderly moral space.

Now, I’ve only scratched the surface – so to speak – of media as urban ‘surfaces’. But I’d like to move on, since surfaces only tell us part of the story in thinking about the media-urban nexus. We also need to think of the depths of the mediated city.

Perhaps the best example of this – whether for scholars, artists or media practitioners – are the hidden urban infrastructures making urban life possible. Every stroll you take on a London pavement, for example, involves walking on an interesting, rich and often curious iconography of plates and markers of infrastructure under the pavement. Telegraphs, telephones, electrics, lighting, television cabling, and so on. And they are signals in the air: WiFi, cellular, radio waves, digitalised microwaves. The traces of which we might find in a structure like BT Tower, built as the Post Office Tower in 1965 to protect ‘line of sight’ for radio waves and microwaves over nearby towers. Communications structures such as these provide a kind media time. Through radio and television programming, sections of day take on certain meanings, domestic environments take on certain dynamics. Interestingly, the BT Tower today remains a communications hub, though less so through aerial transmission. Instead, through historical inertia, it has become base of subterranean fibre optic network servicing the new, on-demand and on-the-move media times afforded by digital television.

We’re not meant to explore or be concerned with these infrastructures; they work best when we ignore them. When they provide us smooth media experiences: of speaking on the phone, or accessing data in the cloud, or just of feeling relatively safe because a street is well-lit. If you’ve read Marshall McLuhan (1964, p. 8), you may recall his example of light itself as a medium – “pure information”, as he said, “a medium without content”. We might say these sorts of urban media infrastructures are offset in space: deliberately removed from our immediate experience. Increased awareness of hidden infrastructures has not only led artists to creatively catalogue the pavement iconography mentioned earlier, but also led urban explorers such as geographer Bradley Garrett to undertake and document subversive ‘place hacking’ expeditions.

But we should also remember that urban media infrastructures in plain view can be offset in time. The most banal of visible urban infrastructures – security barriers, lifts, payment devices, etc – are increasingly scripted by the instructions of software code (see especially Dodge and Kitchin, 2011; Thrift and French, 2002). Here we have not so much hidden physical infrastructure, but hidden urban texts. Texts that function not in terms of symbolic representation, but executable code, read by computers so as to carry out instructions (see e.g. Berry, 2011; Mackenzie, 2006). Where this subterranean language of software code gets interesting – or worrying – is when we begin to think about what it will mean when it goes beyond the operation of mundane urban infrastructure, and begins to approximate corporeal intelligence; to give us, perhaps, a sentient city (see Shepard, 2011).

Now, like with surfaces, I have only been able to superficially think about urban media in terms of ‘depths’. But hopefully by this point we will see how layered a term like ‘mediating cityscapes’ (the term used for this symposium) might be. If we verbally emphasise ‘cityscapes’ – as in, mediating cityscapes – our attention is drawn to the ways in which we experience urban environments through layers upon layers of media: devices, forms, texts, technologies. If, on the other hand, we verbally emphasise ‘mediating’ – as in, mediating cityscapes – our attention is perhaps drawn instead to the ways in which the urban itself mediates, for instance as form, environment or landscape. Indeed, for media theorist Friedrich Kittler (1996), the city is a medium – at least in so far as like all media, it processes, records, and transmits information.

Fragments and Publics

What I’d now like to do in this last section is suggest what the preceding discussion might mean for thinking about mediated fragments and mediated publics – the themes in which we’ve grouped the papers that follow. But I’d like to make a slight shift in emphasis, from a preoccupation with what the media-urban nexus is, to how it unfolds. In our present context, this means thinking about fragments and publics not so much as things, but as processes: as bound up in action, practices, experience. Specifically, I’d like to propose we think in terms of: fragmented attention; and public address. This – I should emphasise – will not necessarily align with the ways in which the subsequent presenters work with these concepts. But it should at least offer one reading – against which the other contributors might respond quite differently. And there is a fringe benefit: it allows me to add a few further examples of phenomena relating to the media-urban nexus; this time, more focused on praxis than materials.

Let’s first think about fragments in terms of attention. One way to thinking about fragmentation in this way is to extend our earlier discussion of urban surfaces one step further, beyond buildings or physical structures. We might also think about how media devices and forms are central to our daily self-presentation in urban settings. In our daily routines, our comings and goings, through the city, you might say we in some ways create surfaces via our media and our bodies. This is so even without any recognisable mediating technology to speak of. Consider the blasé attitude of the urban dweller – famously discussed by Georg Simmel (1903) in his essay ‘The metropolis and mental life’.Urban living means constantly dealing with strangers, and strangeness; regularly confronting a huge range of stimulation vying for our attention at any given moment. For Simmel, the blasé attitude is an embodied coping mechanism in response. It allows the urban dweller to deal with “rapidly changing and closely compressed contrasting stimulations of the nerves.” But this attitude isn’t just a front. It is not merely appearing to ignore, or be unperturbed by, urban stimulation. Rather, it is a bodily, learned means – medium even – of fragmenting one’s attention so as not to be overwhelmed.

You may already see where I’m going with this. If fragmented attention is a necessary, inherent feature of urban living, it is afforded not only through the blasé attitude but a huge range of media. From the Victorian train commuter reading books and newspapers, to the contemporary tube rider playing videos or mobile games, there are a whole series of ways in which we seek to assert some degree of phenomenological control over our everyday urban experience. We create, as Erving Goffman (1963) suggested, ‘involvement shields.’

Digital media introduce further layers of fragmented attention. Early writers on so-called cyberspace, such as William Mitchell (2000), suggested that the digital city would be increasingly characterised by an economy of presence. In other words, increasing demands to choose between face-to-face and digitally-mediated interactions: a process in which we (often only implicitly) weigh the time-space costs and “benefits of the different grades of presence that are now available to us” (p. 129). There’s a virtual/physical dichotomy here that is best avoided. As Gordon and de Souza e Silva (2011) argue in Net Locality, this dichotomy unhelpfully perpetuates a view of media disrupting, or taking us away from, physical urban space. If fragmented attention is really inherent to the urban experience, then it has always been mediated by all manner of technologies – buildings, transport, signs, texts, computation. And here I’ll pivot to a more general point: fragmentation is therefore not just about the constraints imposed by the urban experience; it is also its very condition of possibility.

Let’s turn now to publics. In his book Publics and the City, Kurt Iveson (2007) argues against the established view of his own field, urban geography, in which urban publicness is most often associated with the physical spaces we denote as ‘public’ (e.g. the square, boulevard, piazza, or city park). Iveson argues that we should instead see urban publics in terms of acts, performances or mediums through which publics are ‘addressed’. In this focus on public address, Iveson draws inspiration from queer theorist Michael Warner (2002), who stresses a temporal and circulatory view of publics, defined as the “the concatenation of texts through time” (p. 90). For Warner, publics have a ‘chicken-and-egg circularity’. Addressing a public means taking for granted that such a body already exists: there is something that can be addressed or to which one can respond. Yet every act of public address recreates the same public. Without these acts of public address, there would be no public to which others might respond.

This notion of public leads Iveson (2007) to identify three ways in which publics and the city intersect. First, urban spaces or places often provide venues of public address. Emblematically, we might think of a speaker addressing a co-present audience: speakers corner in Hyde Park; or a speaker shouting through a microphone at a political rally. The urban can also be a venue of public address when co-presence is achieved in space but not in time, for example when someone posts flyers around walls in cities, addressing later passers-by. And yet another way in which the urban can be a venue of public address is as a setting for projection to publics beyond that local site, such as for example theatrical protest practices, meant to attract media attention, possibly further enhanced by the significance of the place it is staged.

Secondly, specific urban spaces or places can become objects of public address. Named localities or types f places often figure as objects for public discussion and debate: for instance held up as ideals; or perhaps identified with problems. We might think, for example, of the many ways in which ‘Brixton’ has been used as a stand-in for all sorts of public debates about London and even the UK: around political uprisings, riots, drugs trade, drugs policing experiments, multiculturalism, gentrification, nightlife, foodie culture, housing, and so on.

A final sense of urban publicness is the ways in which the city can operate as a collective public subject. Very often, ‘the city’ is invoked as a social totality that stands in for ‘the public’. Most commonly, this is where the proper name of the city is used in conjunction with claims to shared interests, values, concerns, turf, etc. This can be politically empowering, or it can involve forms of symbolic violence. Few would say, for example, that the London Evening Standard truly speaks for ‘London’ as a whole, despite the fact that its own claim to legitimacy rests on an amorphous idea of speaking to London in precisely this holistic way.

These three senses of publics and the urban are not mutually exclusive. For example, we might imagine a hypothetical, site-specific installation in Brixton: a montage of archival footage related to 20th century migration to British cities; presented as an exploration of being a 21st century Londoner. Thinking about urban publics as temporalized is not only useful as a corrective against the overly spatialised notions of ‘public’ seen in urban studies or urban geography. It also does the inverse: it brings the notion of public address into contact with its embodied and environmental conditions. In other words, it perhaps gives some material shape to the public sphere (Carpignano, 1999).

Conclusion

Let me bring things to a close. In this opening talk, I have both suggested ways of thinking about the media-urban nexus – in terms of surfaces and depths – as well as made some more specific claims around thinking of mediated fragments and mediated publics in terms of process or experience. But to reaffirm the caution I made at the outset, my intent in so doing has not been to provide a general framework to which the contributions to come are somehow meant to conform. Quite the opposite: I have aimed to propose a few points of reference, some historical or contemporary examples, selected key concepts, and yes, one or two claims. Some of which, I hope, might be of use, or interest, or contention, in the papers that follow.

References

Austin, J. (2010) ‘More to see than a canvas in a white cube: For an art in the streets’ City, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 33–47

Berry, D.M. (2011) The philosophy of software: Code and mediation in the digital age, London: Palgrave.

Borden, I. (2000) ‘Hoardings’ in City A-Z ed. by Pile. S, and Thrift, N. London: Routledge, pp. 104-106

Carpignano, P. (1999) ‘The shape of the sphere: the public sphere and the materiality of communication’ Constellations, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 177-189.

Cronin, A. (2006) ‘Advertising and the metabolism of the city: Urban space, commodity rhythms’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 615-632.

Goffman, E. (1963) Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York: Free Press.

Gordon, E. and de Souza e Silva, A. (2011) Net locality: Why location matters in a networked world, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 85-104

Henkin, D. (1998) City reading: Written words and public spaces in antebellum New York, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 101-135

Iveson, K. (2007) Publics and the city, Oxford: Blackwell

Kitchin, R. and Dodge, M. (2011) Code/space: Software and everyday life, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, see especially pp. 3-22

Kittler, F.A. (1996) ‘The city is a medium’ New Literary History, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 717-729

Mackenzie, A. (2006) Cutting code: Software and sociality, New York: Peter Lang

McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding media: The extensions of man, Abingdon: Routledge

Mitchell, W. (2000) E-topia: “urban life Jim – but not as we know it”, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

Rodgers, S., Barnett, C. and Cochrane, A. (2014) ‘Media practices and urban politics: Conceptualizing the powers of the media-urban nexus‘ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, Vol. 32, No. 6, pp. 1054-1070.

Shepard, M. (ed.) (2011) Sentient city: Ubiquitous computing, architecture and the future of urban space, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Simmel, G. (1903) ‘The metropolis and mental life’ Available at: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/content/bpl_images/content_store/sample_chapter/0631225137/bridge.pdf [last accessed 30/05/2016]

Thrift, N. and French, S. (2002) ‘The automatic production of space’ Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 309-335.

Warner, M. (2002) Publics and counterpublics, New York: Zone Books

0 Comments Leave a comment